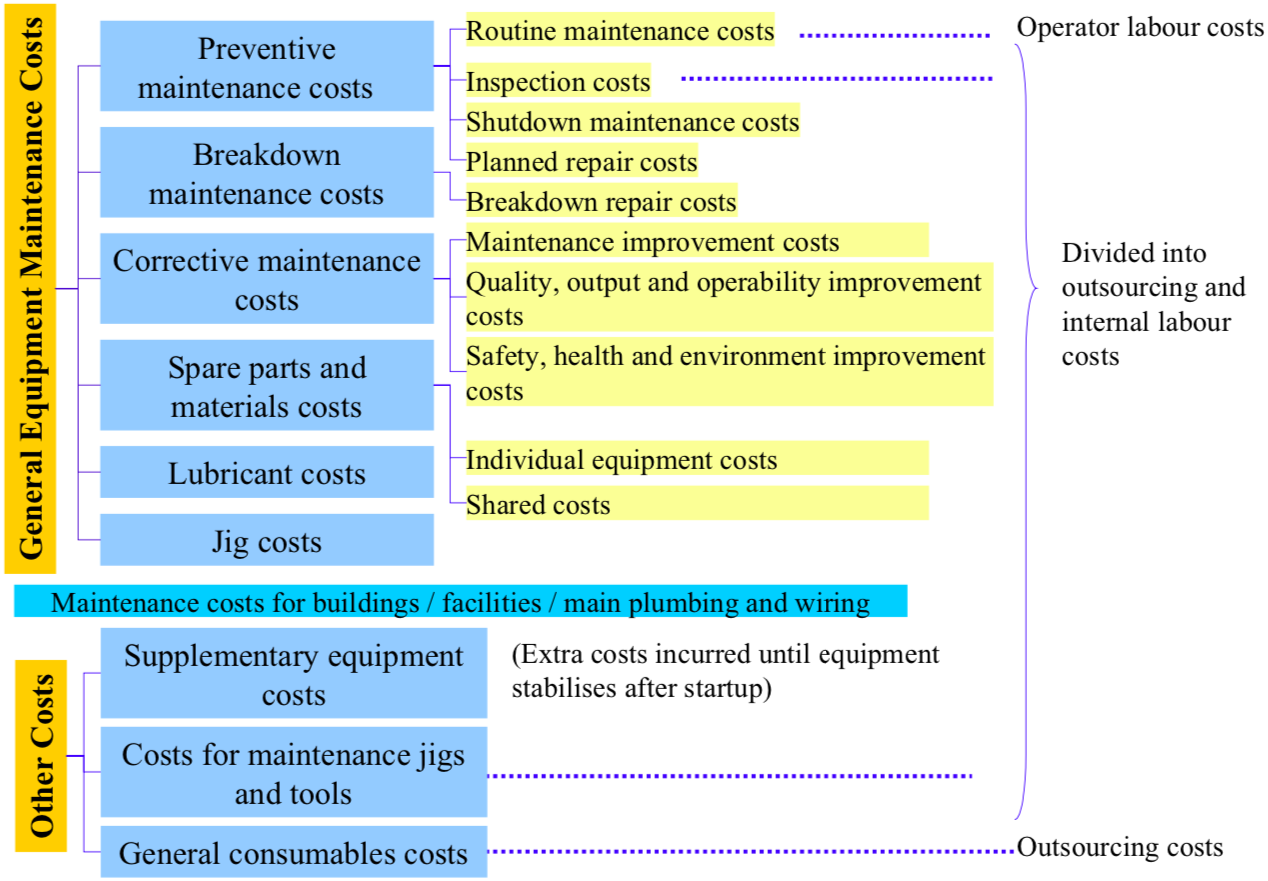

(1) Maintenance cost categories

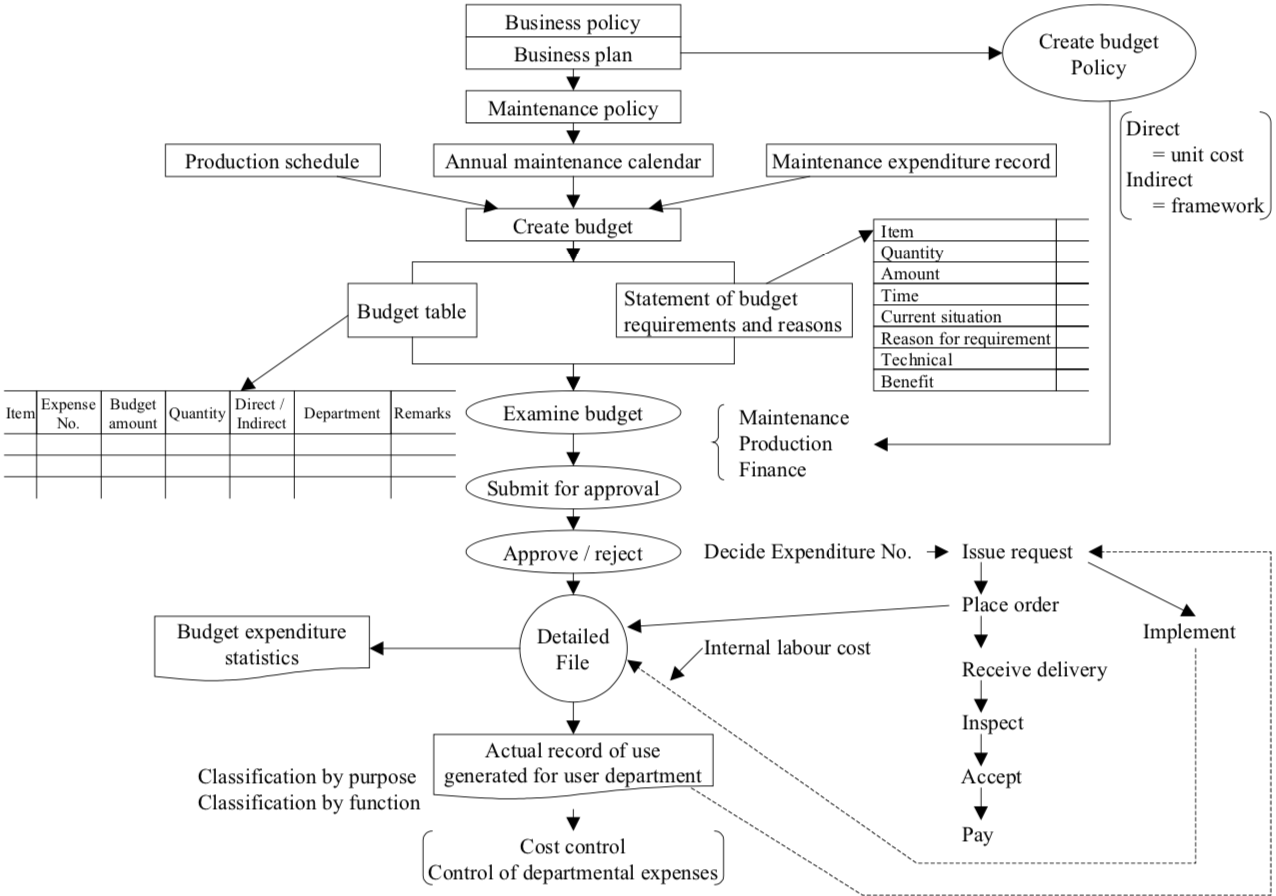

For accounting purposes, maintenance costs are treated as a specific item of expenditure and are generally divided into the sub-categories of material costs, labour costs, outsourcing costs, and so on. However, in managing the maintenance budget, costs should be classified as indicated below, since this will provide much more valuable information for management purposes (see Figure “Classification of Maintenance Costs”).

Classify maintenance costs by:

1 Objective

- Routine maintenance costs The costs of the labor, materials, etc. required to carry out routine maintenance tasks designed to prevent the equipment from deteriorating, such as cleaning, checking, lubricating, and adjusting.

- Equipment inspection costs The costs of the labor, materials, etc., required to inspect equipment for the purpose of identifying abnormalities or evaluating operational performance.

- Repair costs The costs of the labor, materials, etc. required to repair and restore equipment.

2 Maintenance method

- BM (breakdown maintenance) costs

- PM (preventive maintenance) costs

- CM (corrective maintenance) costs

3 Item

- Material costs This category covers the cost of all materials used for maintenance, such as spare parts, general materials, consumables, lubricants, jigs, tools, etc. It is important to break these costs down in further detail.

- Internal labor costs This includes not only the labor costs of maintenance staff but also the relevant labor costs of operators performing Autonomous Maintenance.

- Subcontracting costs The cost of using subcontractors to do maintenance work.

4 Size of job

- e.g. large maintenance projects and small miscellaneous jobs

5 Trade

- e.g. mechanical, electrical, plumbing, instrumentation, etc.

(2) Problems in creating and managing the maintenance budget

1 You are not ‘given’ a budget; you have to take it!

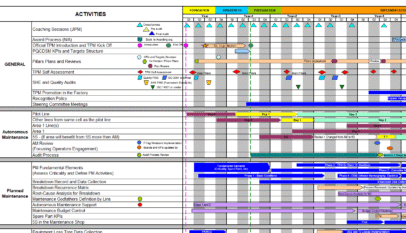

Financial investment is needed if equipment performance and efficiency are to be improved in order to reduce overall maintenance costs and increase profits, and the decision on how and where to spend this money is not the responsibility of the finance department alone. Clear policies and plans for the medium and long term should be drawn up, stating what benefits will be achieved by what spending. These plans and policies will then provide an essential foundation for creating a detailed maintenance schedule and a budget framework based on it (see Figure “Classification of Maintenance Costs”).

2 This means that each expense needs to be categorized according to its precise purpose, both in the proposed budget and the actual expenditure record, and a special effort must be made to reduce it by implementing improvements with the aim of lowering the overall cost. This must be done even if a special temporary budget has to be set up for the purpose.

3 The individual benefits of each item in the improvement plan must be detailed, and the ROI (return on investment) should be estimated in order to justify the proposal.

4 It is pointless having a plan if it is forgotten or allowed to fall behind. Important plans, such as improvement plans, therefore need to be made traceable by incorporating them into the annual maintenance calendar, clearly indicating the person responsible and the work processes involved.

5 Budgets are not cast in stone

Production conditions change all the time; new improvement requirements emerge, and existing ones change, on a daily basis. If there is neither the budget nor the staff to get these improvements done, then the maintenance situation will not advance. It is important to calculate the expected costs and benefits (i.e. the return on investment), always considering the prevailing business environment, and use this information as a weapon for obtaining approval for the necessary changes to the annual schedule (i.e. the maintenance calendar) and budget, and for removing potential obstacles to implementation.

6 Delays in implementing the plan, or failure to achieve the anticipated benefits, are often due to lack of technical capability during the preparation and implementation phases. Qualified people from relevant departments must be employed from the outset to make the most of the technical information available, from both internal and external sources. It is up to managers to ensure that this takes place.

7 Results must always be evaluated and used for selling the benefits of maintenance since it generally has too low a profile.

(3) Keys to reducing maintenance costs

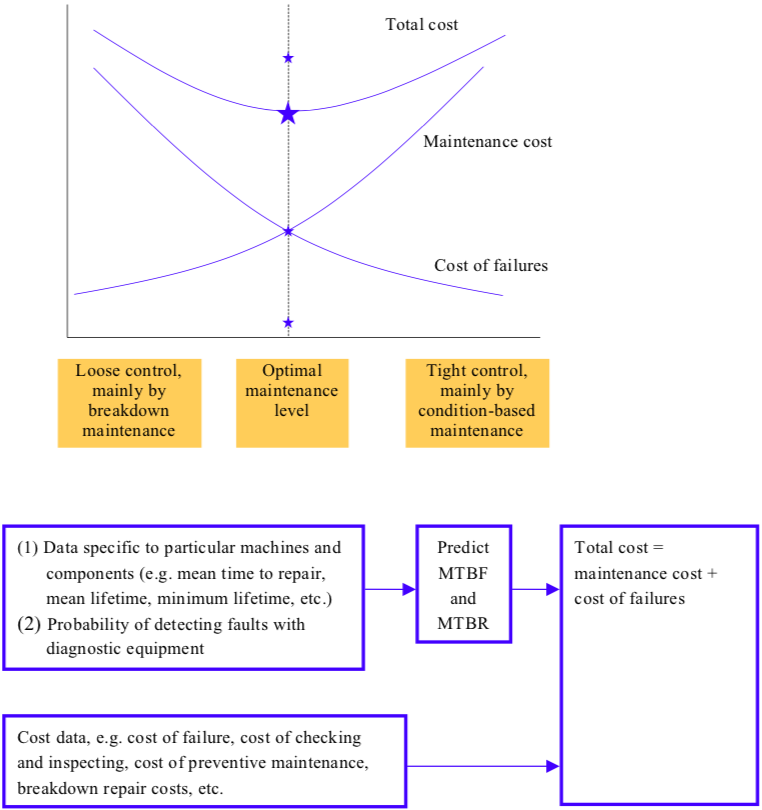

It is not going too far to say that all companies have scope for reducing their maintenance costs, to a greater or lesser extent. The focus for cost-cutting will vary in each company, depending on the sector it works in and the equipment it uses, so it is hard to make sweeping generalizations, although VE (value engineering) often proves to be a very useful approach. Maintenance cost reduction is discussed from a general perspective below (see Figures “Creating and Managing a Maintenance Budget (example)” and “Cost Balance”).

1 Review frequency of periodic servicing

The different sections and components of a machine do not all deteriorate at the same rate, and the intervals for periodic servicing and overhaul are usually determined by the part having the shortest working life. Servicing intervals often become fixed out of habit, to once every 6 months or 10 months, for instance, and must be revised comprehensively from time to time. It is also important to move progressively from time-based maintenance to condition-based maintenance, by introducing equipment diagnostic techniques.

2 Bring subcontracted work in-house

Preventive maintenance tends to account for the largest share of maintenance costs, with outsourced repairs, in particular, representing the principal cost. If this is the case, and there is too great a dependence on subcontracting, then maintenance technology and skills will flow out of the company and it will be unable to build up its own body of preventive maintenance expertise. The key, therefore, is gradually to bring the subcontracted tasks in-house.

3 Review spare parts

Maintenance stores often contain a much larger stock of spare parts than the annual budget would appear to warrant. In some cases, valves, flanges, V-belts, and seals are held in stock for as long as two or three years, and some of them deteriorate functionally even before they are used. Even when the stock of spares is controlled by the order-point method, the order points have often been decided several years before and are unsuited to the current situation. It is important to reduce the number of spares held permanently in stock, whilst increasing the number of those bought in as needed.

4 Make effective use of idle equipment

The old throwaway mentality meant that equipment was often discarded and replaced as soon as it began to get a bit long in the tooth, but we now need to be much more prudent about how we consume our natural resources. This means thinking carefully about ways to reuse or recycle equipment, rather than simply throwing it out. For instance, a plant may have a large number of pumps and motors that it no longer uses, but this does not mean they no longer have any value. It is worth exchanging information with other sites to see whether such equipment can be used elsewhere.

5 Reduce loss of energy and other resources

A quick tour of any site will always reveal energy losses of some kind, whether they result from leaking oil, air, steam, or water, lights left on all the time, or furnaces or motors left running when not in use. There will also be many instances of wasted resources, such as raw materials being scattered, spilled, or damaged.

6 Eliminate equipment losses

Equipment is also the source of considerable financial losses. After an unexpected breakdown, energy losses and yield losses will be incurred until the equipment is fully up and running again, and if a machine’s performance drops, it may start to produce quality defects. Such financial losses can be greatly reduced by introducing TPM and maximizing equipment efficiency.