(1) They are often abandoned after unsuccessful attempts to cure them

The causes of chronic quality defects are notoriously difficult to pin down. As a result, teams often attempt solutions without understanding the true causes of the problem; the situation consequently fails to improve, and the attempt is abandoned. Various excuses are put forward for giving up, such as that it is impossible to find a solution without knowing the cause, or that the equipment concerned is so badly designed that there is no way the problem could be fixed, but generally speaking the following mistakes are made:

1 Taking the wrong approach:

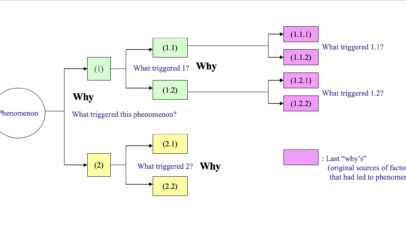

When faced with a problem, we always seem to assume that there must be a definite cause and focus our efforts on finding it. This approach inevitably leads us to make up our minds what the cause must be, or at least to narrow it down to a few possibilities and concentrate on eliminating those. However, as explained earlier, chronic quality defects are due to multiple causes that differ from occasion to occasion, so tackling only a few of them is not usually very effective. What needs to be done is to eliminate anything that could reasonably be suspected of being implicated in the problem, but this is not usually practised thoroughly enough.

2 Studying the phenomenon from a blinkered technical viewpoint (a mistake often made by qualified engineers):

A problem common to many companies is that when expert engineers investigate a phenomenon, they tend to restrict their thinking to their particular area of expertise. This leads them to complicate the issue; they fail to find a solution to what is really a relatively simple problem and eventually abandon the attempt.

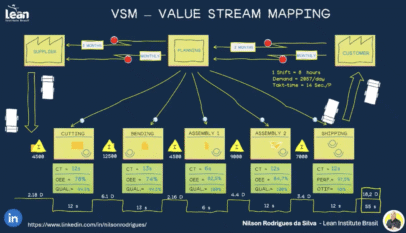

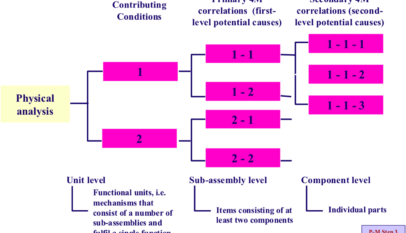

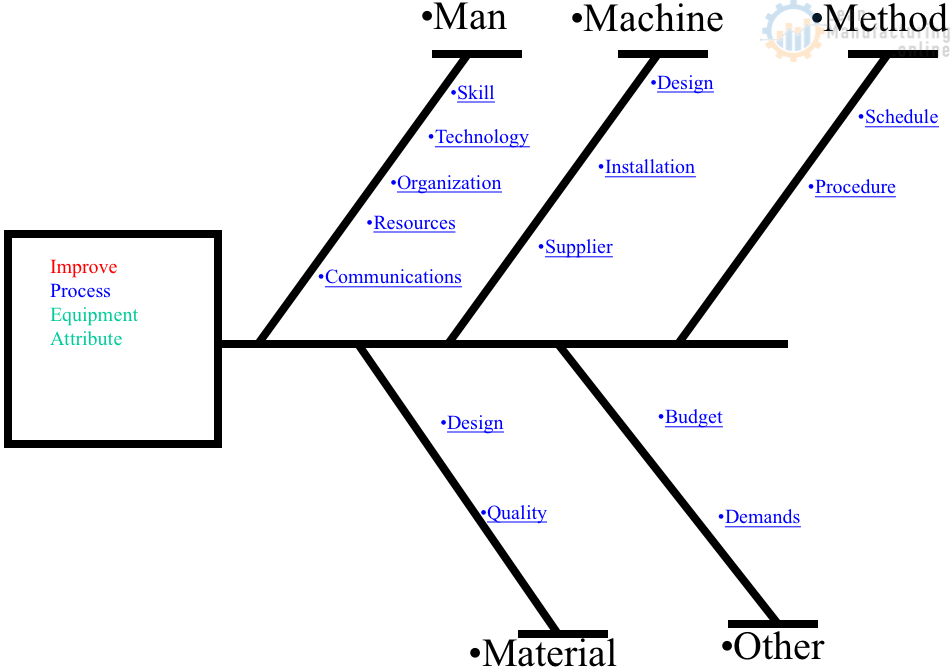

Some quality defect problems can be solved by the application of specific engineering technology, but in most cases, this is insufficient. The way in which the machine is treated on a daily basis by the people responsible for operating and maintaining it must also be included in the equation. A single problem phenomenon is governed by a multitude of factors on the production floor, any of which could change at any time and give rise to the problem. The rate of quality defects after a changeover, for example, will depend on how the changeover is done, how the adjustments are made, how the parts are installed, how the processing conditions and clearances are set, and so forth. Engineers need to develop their ability to observe the equipment itself, the way in which the shop floor works, the way in which changeovers and adjustments are carried out, and so on. They need to be able to spot the variables in the work and the equipment.

When much time and effort have been spent on introducing a specific technology but the results are inconsistent or not as good as expected, the problem usually lies at the interface between the technology and the way in which it is handled from day to day.

Many more problems could be solved if tackled by a combination of the shop-floor and engineering approaches, rather than by the engineering approach alone.

(2) Possible causes are not identified or analyzed adequately

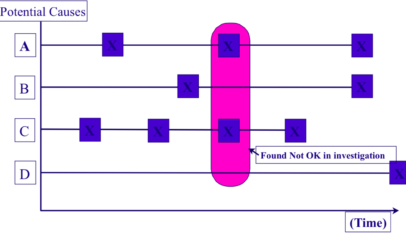

Another common problem when tackling quality defects is the lack of skill at identifying the relevant factors (the control points) and lack of skill at analyzing them once they have been identified. The first of these is due to inadequate observation and analysis of the problem phenomenon, misapplication of analytical techniques, making deductions based solely on past experience, or, as discussed earlier, overlooking relevant factors by jumping to conclusions about the causes. The second is due to managers’ and engineers’ inability to see exactly what is going on with the equipment and the process; that is, their inability to recognize deficiencies (deviations from the optimal) and understand their effect on the problem phenomenon. Because of this inability, deficiencies or their warning signs go unnoticed, and nothing is done about them because they remain undefined. The result is uncontrolled chronic defects. The only way to improve a situation like this is to do a comprehensive review and deep analysis of all possible relevant factors.

Sporadic Defects and Chronic Defects

A sporadic defect is a sudden undesirable change that requires some action (such as replacing a worn jig) to restore the status quo, while a chronic defect is a prolonged undesirable situation that requires some action to alter the status quo. In the first case, we are trying to maintain the existing situation, while in the second we are trying to break out of it.

Being different in nature, sporadic and chronic defects require different approaches: the former is the joint responsibility of operators and managers and requires restorative action with the aim of getting the results back to what they were before, through comparison with existing standards and by checking control points; the latter is a management responsibility and requires ameliorative action to break through and change the situation with the aim of achieving new policy-led targets, by revising the standards and control points and setting new ones where necessary.

Sporadic defects occur when existing control points and causal factors change suddenly; they are resolved by restoring the variable factors to their original state. Chronic defects, on the other hand, are not reduced by complying with the original control points or causal factors; completely different ones have to be established and adhered to. This requires breakthrough thinking.

Existing causal factors must be controlled much more strictly, new control methods must be introduced to ensure that deficiencies are not overlooked, and other as-yet uncontrolled causal factors must be investigated.

Very helpful article! It highlights common challenges in quality improvement and provides insight into how to deal with chronic quality defects. The points made about the importance of understanding root causes and avoiding a narrow view of technical problems are critical for any team seeking continuous improvement.