2.8 Using Safety Tags and Maps

(1) Safety tags

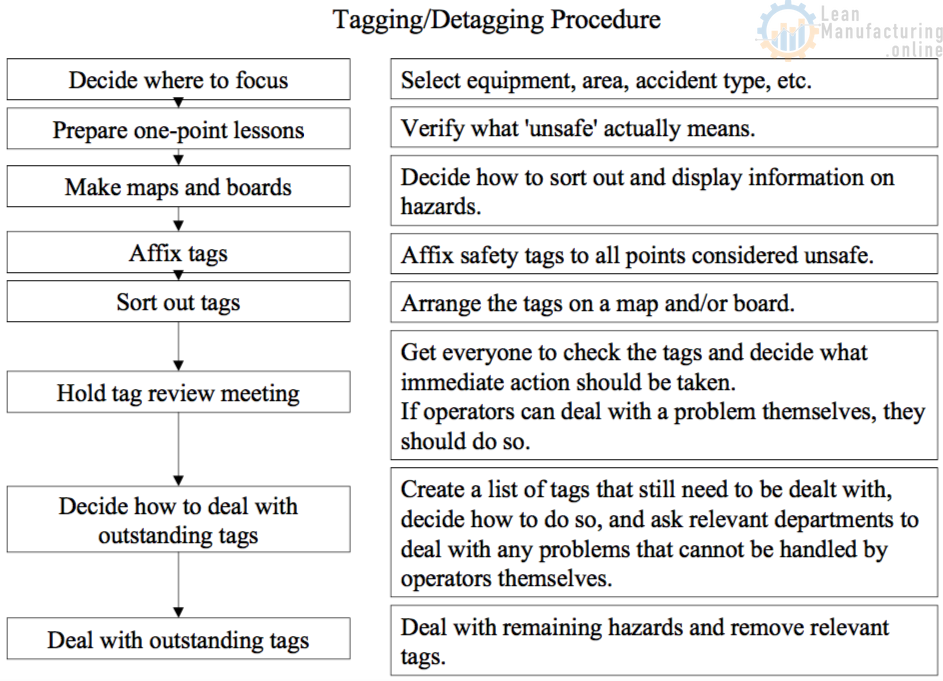

If an on-site safety inspection reveals a hazard, but nothing is done about it, the inspection will have served no purpose. Also, if the hazard is not clearly indicated, a person doing a safety check at a later date will not know whether they are discovering it for the first time, or if it has already been noticed. A factory obviously needs a way of letting everyone know exactly where and when the safety hazards were identified. It also needs to ensure that anyone can see at a glance which ones remain to be dealt with. (see Figure 11.8)

A system of safety tags is very useful for achieving this. The tags used are about the size of a baggage label, are often coloured yellow, and carry a warning such as ‘UNSAFE’. When a hazard is found, the information listed below is written on a tag, which is then attached to the location of the hazard. Observers should go ahead and tag anything they consider unsafe – the question of how it can be made safe is addressed later.

Typical information entered on tag:

- Location

- Date identified

- Identified by

- Description of hazard

(2) Maps and boards

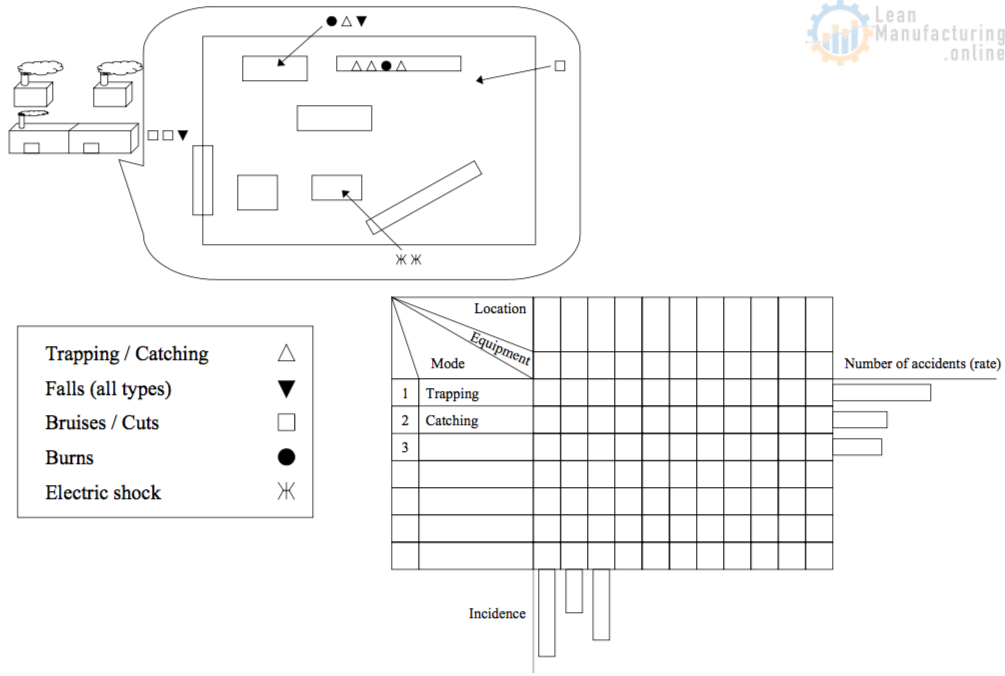

In reality, it is often impractical to attach tags directly to machines, tools, locations or tasks. In such cases, attaching the tags to a map of the area can make the situation very visible and easy to understand. A board can also be used to arrange the tags in order.

(3) Tag lists

Once tags have been assigned, and the hazards have been organised on a map and/or board, the information can then be compiled in the form of a list. The tagged points are then rectified one by one, following the list. It is important to do this at each step, until it becomes a matter of routine.

2.9 Examining Past Accidents and Analysing Data

Investigating and analysing past accidents can highlight the particular characteristics of the accidents that tend to occur at the company, allowing any ingrained features hampering safety to be recognised. The procedure described below should be followed.

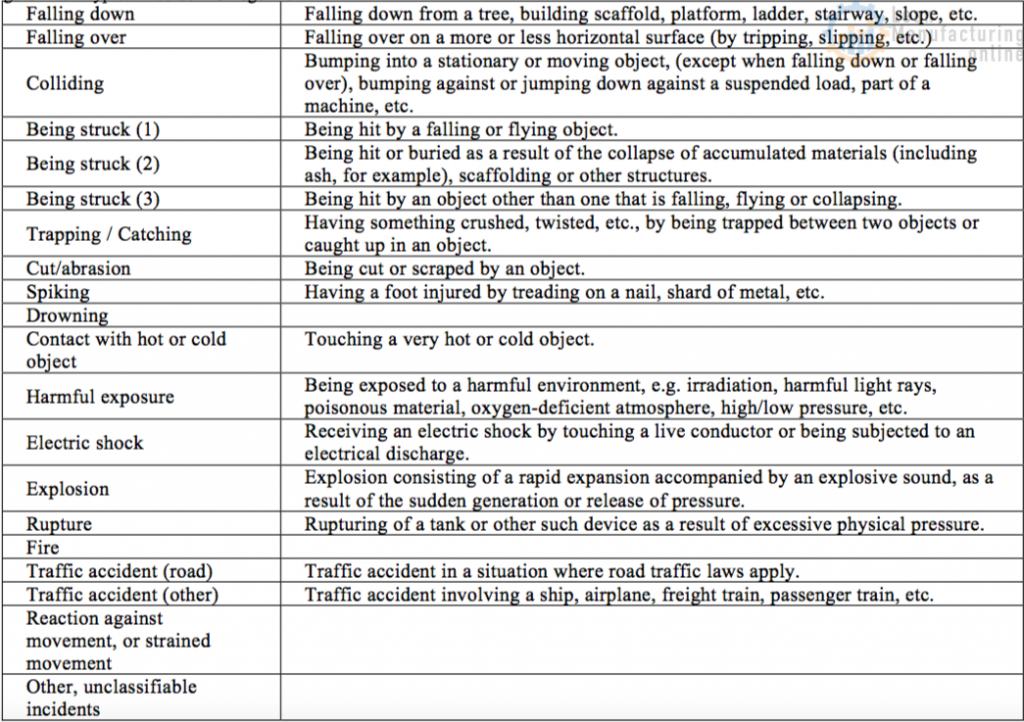

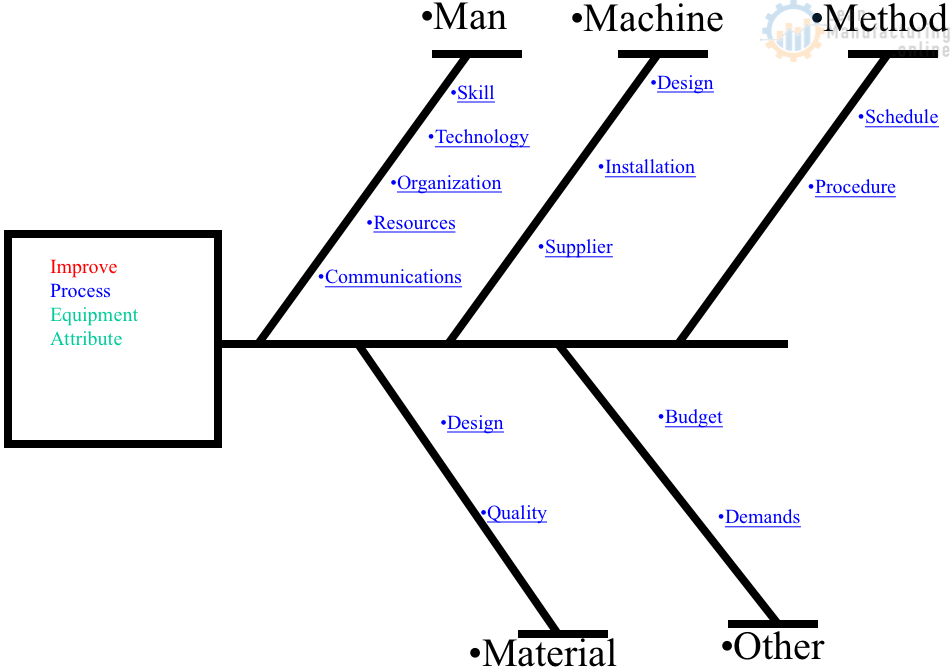

(1) Categorise accident scenarios and define their titles and contents (see Figure 11.9).

(2) Define the perspectives from which accidents will be analysed, and sort the data into the relevant categories:

Analyse past accidents, but only those that fit into a precise perspective and cause category. If the analysis process throws up any items that are unclear, then do not speculate about what might be involved. Possible analytical perspectives include: accident scenario, equipment / part where accident occurred, relevant time band, age of operator, number of years’ experience, job category, part-time / full-time, etc.

(3) Record the locations of past accidents and near misses on a map of the workplace (see Figure 11.10).

The latter part of this chapter provides reference information on various topics, such as protective equipment and how it should be used, safety devices and how they should be checked and repaired, strategies for dealing with various accident modes and problematic areas, safety management systems and emergency response systems, and safety awareness programmes.

Figure 11.8 Tagging / Detagging Procedure

Figure 11.9 Typical Accident Categories

Figure 11.10 Example of Incident Map

3. Creating Worker-Friendly Workplaces

TPM is designed to build a robust corporate environment that manifests high levels of production efficiency by exposing losses such as waste, inconsistency and strain arising anywhere within the operation, and finding ways to make suitable improvements. Making workplaces more worker-friendly is essential for enhancing safety and is an indispensable part of the TPM initiative.

3.1 The Need for ‘Humanware Management’

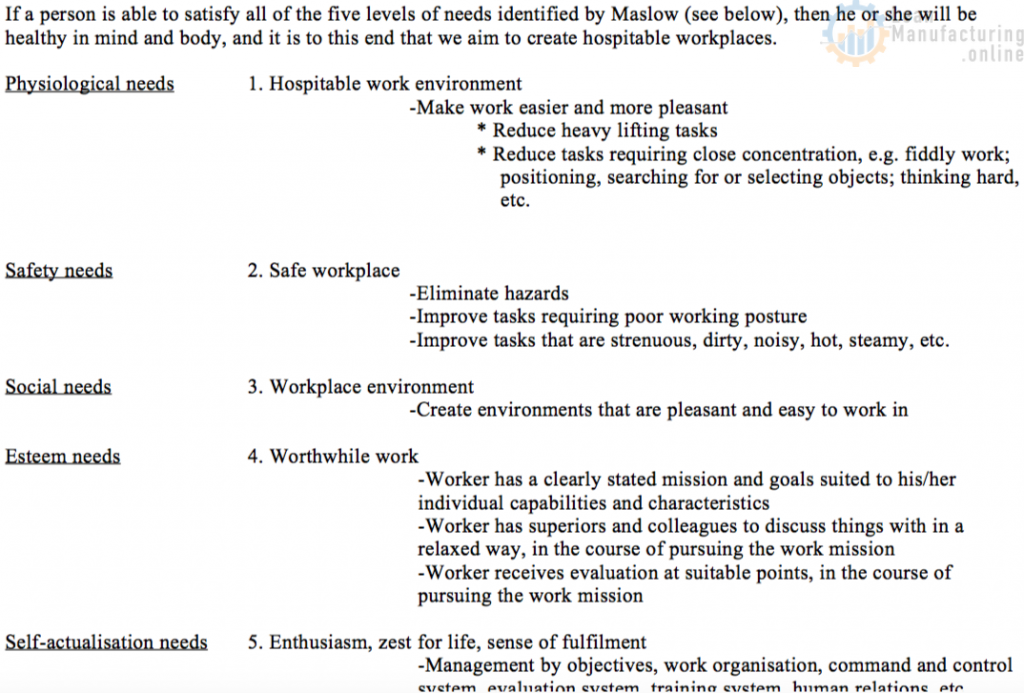

According to the American psychologist Abraham Maslow, humans have a five-tier hierarchy of needs: physiological needs, the need for safety (including needs relating to our basic work environment), social needs (the need for affection and a sense of belonging), the need for self-esteem and recognition, and the need for self-actualisation, which relates to human relationships and communication (see Figure 11.11). The conditions required in order to satisfy these needs may be equated with the basic conditions required for people to function efficiently. Companies should try to create factories and machinery that are ‘people-friendly’ by implementing ‘humanware management’; that is, management aimed at satisfying these basic conditions.

Figure 11.11 Developing People-Friendly Equipment and Workplaces – Definition and Objectives

3.2 Assessing the Working Environment and Making Improvements

Any aspects of the workplace that are unsatisfactory from a health or environmental standpoint must be identified and rectified by making improvements wherever possible. The working environment should be progressively enhanced so that it becomes more and more conducive to the job in hand, and improvements must drastically reduce anything harmful to workers’ health, such as noise, high temperatures, dust, and so on. The impact of the company’s operations on the surrounding neighbourhood must also be diminished.

In order to establish standards for the work environment and create a pleasant and hospitable workplace, it is necessary to:

- Maintain a pleasant working environment

- Arrange things so that people’s movements and work operations are rhythmical

- Provide equipment and facilities that counter stress and fatigue. Starting by doing whatever can be done in these three areas, standards should be set with regard to noise, heat, physical exertion, dust, lighting, etc., and ongoing improvements should be made. Hazardous substances and control categories must also be clearly indicated.

3.3 The Five Basic Conditions for Being ‘People-Friendly’

By establishing basic people-friendly conditions in their equipment and systems, companies can improve employee satisfaction and the rest of the 4 Ss (customer satisfaction, social satisfaction, and financial satisfaction, i.e. cash flow), while turning themselves into highly creative organisations with calmly efficient working environments. This is the path to achieving high quality and high productivity.

The five basic conditions for a people-friendly environment:

- Work that does not cause fatigue to build up

- Comfortable, safe, healthy working environments

- Safe workplaces where human errors are not liable to occur

- Workplaces that are also welcoming to older employees

- Workplaces that allow employees to enjoy creativity, zest for life, and satisfaction in their work

When seeking to establish the basic people-friendly conditions described above, the current situation has to be identified to see exactly what state the workplace is in at present, and expose any deficiencies that must be corrected. This is similar to the target- based approach for raising OEE adopted in TPM. Reference materials are provided at the end of this chapter to assist companies to create hospitable work environments that alleviate worker fatigue.

4. Towards a Recycling-Oriented Society

A ‘recycling-oriented society’ has been defined as ‘A society in which the consumption of natural resources is controlled, and the load on the environment minimised, by preventing industrial products from becoming waste, promoting the appropriate recycling of recyclable products and materials, and ensuring the appropriate disposal of non-recyclable resources’.

The basic approach required to achieve this is described in the following terms: ‘A recycling-oriented society is to be achieved by encouraging autonomous, forward- looking action to this end in accordance with economic and technological possibilities, with the goal of realising a society capable of sustainable development while fostering the growth of a healthy economy that has minimal impact on the environment.’.

Based on this concept, in TPM we do not stop at simply trying to reduce the amount of waste our factories generate, but attempt to prevent all forms of environmental pollution, of which waste is but a part.

4.1 Global Environmental Issues and Pollution

(1) Reflections on the consumer society

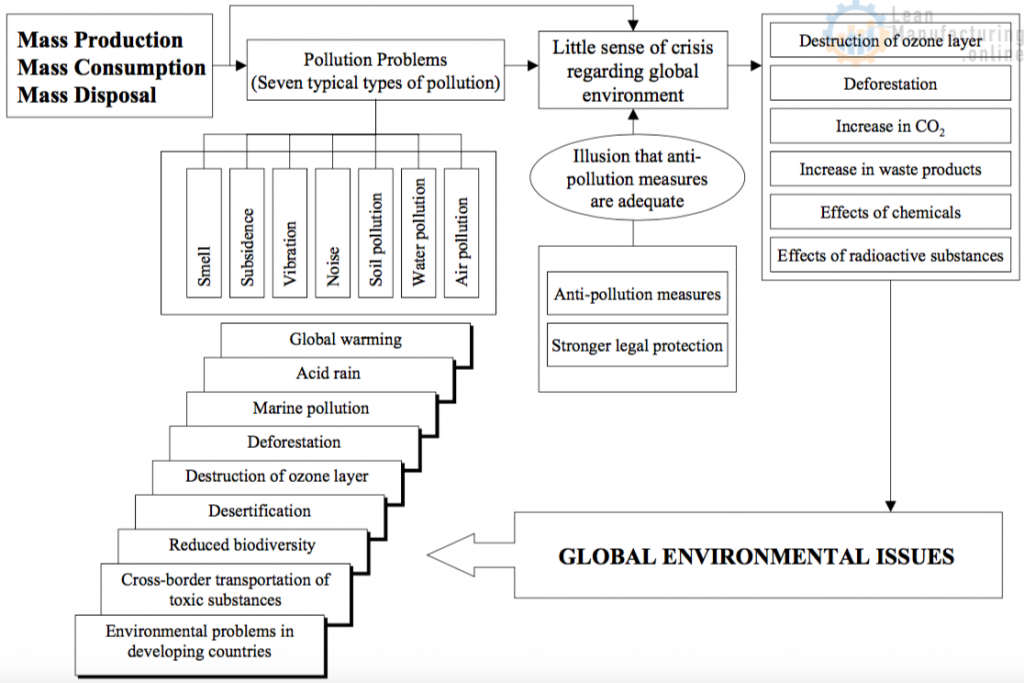

The 20th century has been one of material civilisation. Human beings have sought a purpose of some kind in their lives by trying to satisfy their needs through the acquisition of material goods. In this way, we have created an overwhelming trend towards a ‘mass-producing, mass-consuming, mass-disposal’ society premised on the assumption that we have an inexhaustible supply of resources, that contamination can be controlled by nature and its inherent capacity to clear up our pollution, and that we can basically throw things away to our hearts’ content.

Pollution problems started to emerge from the 1950s into the 1960s and 70s. These problems arose as a result of the lack of effective legal protection for citizens’ health and living rights, coupled with the business world’s overriding obsession with production and profit. What is more, whenever a case of pollution has occurred somewhere, at home or abroad, there has been an undeniable sense of complacency, with those who are not directly involved seeming quite happy to stand by and watch others suffer the consequences. Many problems of this kind have now been addressed by the introduction of much tighter legislation, and the anti-pollution measures that have been adopted by industry.

This history highlights a unique characteristic of pollution as an issue, namely, that there is an offender (or polluter) who generates the pollution, and victims who suffer some sort of physical harm, infringement of their basic living rights, and so on, as a consequence of this pollution. The existence of this two-way relationship has meant that the various measures pursued have always been based on legal standpoints and policies.

This may well have given us the idea that we have overcome the problem of pollution, but the fact is that the effects of commercial activities have simply moved beyond the sphere of local pollution to a stage where they now threaten the global environment as a whole.

The greatest problem facing us today is that our living environment is undergoing massive change, and yet we can no longer establish a simple relationship between ‘offender’ and ‘victim’ in the same way as when dealing with past problems of pollution. Put simply, each one of us is both offender and victim. This is the defining feature of the environmental question: it has to be addressed from a truly global standpoint that reaches all the way from individuals through organisations to society as a whole. This is a perspective that we have never had to adopt before (see Figure 11.13).

Figure 11.13 Reflections on the Consumer Society (from local pollution to the global environmental issue)

(2) The special characteristics of the environmental question

As discussed above, the issue of the environment differs from that of pollution in several key aspects. The principal differences are:

- The effects are not readily visible, so it is difficult to appreciate the problem as real and tangible.

- No ‘offender-victim’ relationship exists.

- Our responsibility is owed more towards future generations than to the present one.

- The environmental question affects the right to survival of other species, apart from humans.

- Contamination and destruction of the natural environment is a problem that crosses national borders.

- Everyone, from individuals through to organisations of all kinds, is expected to display the highest morals and standards.

The most important of these factors, in terms of its impact on our awareness and behaviour, is the fact that under normal conditions, it is very difficult to gain a real sense of how serious the effects on the environment are. We used to tell ourselves that these problems were not urgent and could be dealt with later, and there was a certain degree of tacit connivance behind this procrastination. From here on, however, this type of thinking will simply not be acceptable. The price for everything we have achieved in the 20th century has been the destruction of the environment, and it is an issue that we have a duty to resolve for the sake of future generations.

4.2 The Responsibility of Industrial Producers

Any country that wants to work towards becoming a ‘recycling-oriented society’ does of course require the full and active involvement of producers. As producers, we should remind ourselves that we have a clear and unavoidable responsibility in helping to prevent environmental contamination. Business leaders must therefore bear the following issues clearly in mind when looking to develop their operations in the future.

(1) Preventing pollution

The key to protecting the environment lies in prevention. This requires producers to engage in ‘anti-polluting’ activities such as:

- Designing products that do not end up as waste

- Reusing waste products as resources

- Recycling waste materials for repeated use

- Reducing the generation of environmental contaminants

- Reducing the use of harmful chemicals and handling them appropriately

- Reducing the consumption of resources and energy

Ways must be found to work these initiatives into the core ‘business process’ of making products, so that they become routine business activities, and they must be managed from the standpoint of prevention. Management systems must also be setup to ensure that the necessary steps are indeed taken to protect the environment. This means that companies are faced with three key requirements: to set up systems to prevent problems from arising; to manage these systems so that problems do not arise; and to ensure the feedback of relevant information in the event of a problem so that the systems can be revised if necessary. By implementing this approach painstakingly and perseveringly, the goal of preventing pollution can be achieved and sustained.

(2) Disclosing information

In some cases, isolated incidents have undesirable effects on the environment. In others, it may emerge that a company is having a cumulative effect over time on the people living in the surrounding area, as a result not of isolated incidents but of normal everyday operations. In all such cases, it is vital for the company to provide prompt and accurate information about accidents or emergencies to those potentially affected, as well as explaining, clearly and frankly, the basic philosophy underpinning the company’s business operations, the current situation as it stands, and the future prognosis. The demand for such information is now becoming stronger than ever.

A firm’s attitude to the disclosure of information is likely to become an extremely important factor when its future prospects are evaluated in the marketplace. Today, corporations are coming under ever closer scrutiny with regard to their moral stance, and the environmental issue has become one of the key items by which companies are judged. In the future, we can expect this ‘environmental rating’ to have a huge impact on corporate affairs, from stock prices, finance, and recruitment, through to the incentives a company is offered to site its plants in particular locations.

(3) Obeying the law and implementing self-regulation

In many cases, statutory regulations are determined in light of the possibility of effective response – that is, by the prevailing technical standards. It follows that the standards stipulated in law are not necessarily the most desirable ones for the people affected. This means that, from a logical viewpoint, obeying the law is the minimum obligation, and properly speaking, the producer should aim for a higher level than this. Self-regulation and self-imposed standards will become increasingly important – in other words, companies will be expected to take positive action to achieve standards above and beyond those required by law – in areas such as wastewater quality, exhaust gas concentration, soot and dust density, noise, vibration, soil contamination, and so on. These obligations are what ‘risk management’ really means for organisations. Indeed, analysis has revealed that many of the recent business scandals have been caused in large part by companies’ failures to take their responsibilities in these areas seriously enough.

4.3 Strategies for Achieving a Recycling-Oriented Society

One of the key phrases that frequently crops up in the environmental debate, and particularly in relation to manufacturers, is ‘zero emissions’. Literally, of course, this means just what it says – zero release of industrial waste products – but the phrase is usually employed in a far broader sense to indicate an economy, society, community, business activities, etc., that do not produce any waste. The idea of zero emissions is in fact not limited to the absence of waste, but rather describes a holistic attitude that gives priority to coexisting in harmony with the natural world, treating material objects with care, building products that last, and recycling products when they are no longer usable. Indeed, ‘zero emissions’ is a key phrase for building a new type of civilisation, based on the recognition that the world’s resources are finite.

One practical development from this is the recent increase in companies aiming to create ‘rubbish-free factories’. By eliminating waste products from the factory, these initiatives represent a first step towards achieving ‘zero emissions’ at the company or worksite level.

A large number of companies have been able to achieve ‘zero-emission factories’ as a result of introducing and developing TPM. However, this type of proactive approach is still relatively rare in manufacturing circles, and in many cases, individual companies do not have sufficient drive or momentum to achieve zero emissions on their own. For the generator of waste products, the greatest barrier to recycling them into usable resources is the high cost of processing the waste. Another major problem is lack of information about companies ready to accept and treat waste, and about new environment-related technology and equipment.

Problems relating to the recycling and reuse of industrial waste products can be very hard to tackle independently at the worksite level, and the JIPM has therefore proposed the creation of an inter-regional, cross-industry, zero-emission network or ‘loop’ to help resolve them. The functions provided by this ‘loop’ can be used by industry to forge cooperative links between the providers and receivers of waste products, and drive towards achieving ‘zero rubbish’ on various fronts. In this, it is vital to garner the participation of regional authorities, government bodies and individual experts ready and able to share their own particular technologies and know-how. We see this as one of the key undertakings for producers in the future.

4.4 Creating a Recycling-Oriented Society through TPM

As mentioned above, creating a recycling-oriented society requires a whole range of different initiatives, starting with the ‘3 Rs’ of prevention (reduce, reuse, recycle). At the same time, companies must work to restrict their use of harmful chemicals and ensure they are handled correctly, reduce their consumption of energy and resources, develop their emergency response capabilities, give workers environmental training, and ensure that the relevant legislation is obeyed.

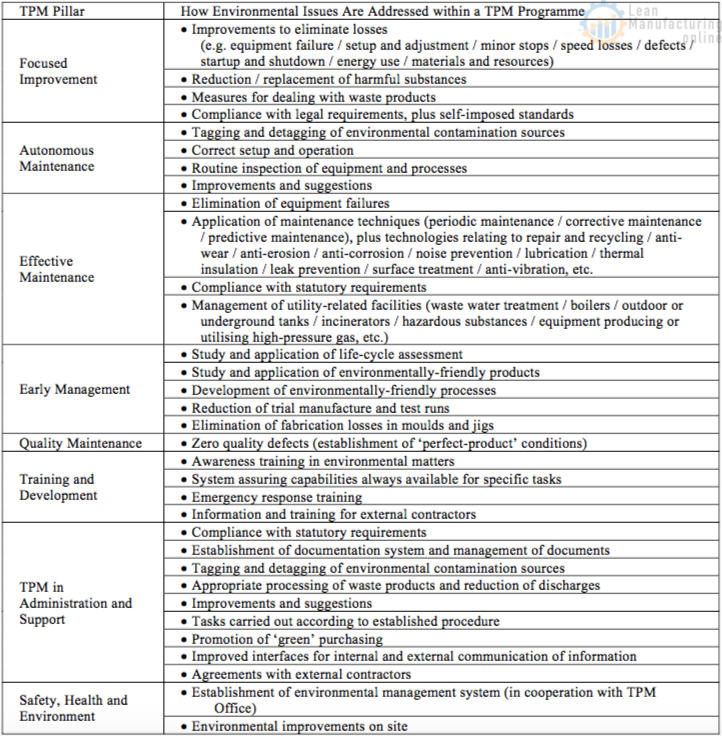

The eight pillars of TPM are designed to match the business processes involved in manufacturing products, and therefore provide an efficient and effective programme suited to the functions of those processes. If environmentally-oriented activities are also to form ‘part of the job’, it would seem logical to adopt a system in which these activities are incorporated into the existing eight pillars, and developed within the TPM framework. Table 11.2 shows one example of how environmental activities might be deployed in this way.

Table 11.2 Tackling Environmental Issues within TPM

TPM encompasses a range of different initiatives, aimed variously at preventing equipment breakdowns and minor stops, stabilising quality, achieving right-first-time setup, starting up quickly and stably, operating processes at their design speeds (or faster), eliminating idling, achieving right-first-time commissioning of new equipment, compressing design and development times, raising the yields obtained from tools, moulds and jigs, preventing air and steam leaks, and so forth. Each of these activities also serves to improve environmental performance.

What is more, many of the equipment maintenance techniques introduced in order to do things such as implementing routine checks and periodic inspections; extending machine and component life; managing lubrication; isolating heat, vibration and noise; and repairing and renewing equipment, also link directly to protection of the environment. The same applies of course to any action taken to reduce the consumption of energy and resources and the generation of waste products.

However, the environmental question throws up a great number of new issues, and ways must be found of introducing these into the TPM programme and developing them within it. These new topics include, for example, the creation of an environmental management system; the training and development required in order to carry out environment-related tasks; the development of emergency response capabilities; preventive measures; the appropriate management of harmful chemicals; and measures to ensure legal compliance and evaluate related performance.

4.5 The Importance of Building an Environmental Management System

(1) Gaining ISO 14001 certification

Setting up an environmental management system has become an essential requirement for businesses and other organisations. This means promoting systematic and consistent programmes of activities to ensure that the organisation’s operations do not have a harmful effect on the environment.

A company’s environmental management system will be more effective if it is designed in accordance with the ISO 14001 specifications. Basing the system on ISO ensures third-party recognition, and allows the company to publicize the fact that its environmental management system complies with known international standards.

The aim here is not the ISO label for its own sake, but rather the company’s commitment to operate in a way that respects the environment, systematically, throughout the organisation, starting with the top management and involving all of the employees. The company pledges to outsiders that it has constructed its system in line with ISO14001. Any organisation that has set up and implemented an environmental management system or intends to do so, must therefore position this as a central part of its basic work activities. Just as with TPM activities, ways must be found to incorporate everything stipulated in the environmental management system into everyone’s everyday duties, making it just another part of their job.

(2) ISO 14001 registration audit and self-declaration

A great deal of attention has been paid to gaining ISO 14001 certification, but for small and medium-sized businesses in particular, the costs involved in achieving it, and the task of setting up an effective structure to promote it, have been major barriers to the introduction and implementation of the standards. However, a relatively unknown feature of the ISO 14001 specifications is that they also allow for ‘self-declaration’ as well as for third-party registration.

In the self-declaration process, an organisation itself decides that its environmental management system complies with the provisions of ISO 14001, and makes a public declaration to this effect. Of course, any organisation, anywhere in the world, will have an innate tendency to be more lenient on itself, and stricter on others, and the ‘self’ element of self-declaration and self-certification implies that there is little to corroborate the objectivity and reliability of the system that has been put in place. For this reason, self-declaration has not yet been widely adopted in many countries including Japan.

However, if an organisation aiming to self-declare were able to receive objective evaluation from a third party, then it could announce with full confidence that it had built and maintained a reliable ISO-compliant environmental management system. This type of external assessment makes self-declaration a practical option, and we can expect the system to spread in this form in coming years.

The JIPM operates a ‘self-declaration assistance scheme’ for objectively assessing and certifying sites that have opted for self-declaration, and this scheme can be used effectively by firms to validate and publicise the systems they have built. What is more, the assistance scheme is not limited to the declaration phase, but can be also be used in the building, implementation or sustainment phases, thus making it possible to construct an environmental management system in a short space of time with minimal effort.

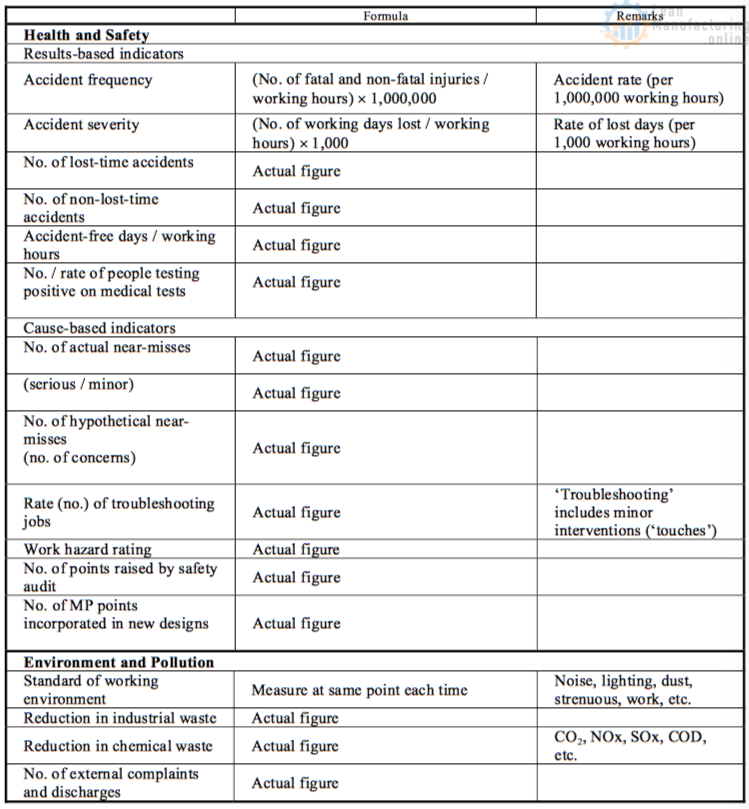

5. Management Indicators

All activities must produce a result of some kind, and the SHE (safety, health and environment) field is no exception. Indicators for evaluating safety, health and environment should be published and used to drive the PDCA cycle towards the desired goals. Table 11.3 gives an overview of some result-based SHE indicators, as well as some cause-related indicators that translate into improvements in the result indicators, and examples of the formulae used to calculate these. These measures form a good starting point for identifying your own company’s shortcomings in this field.

Reference 1

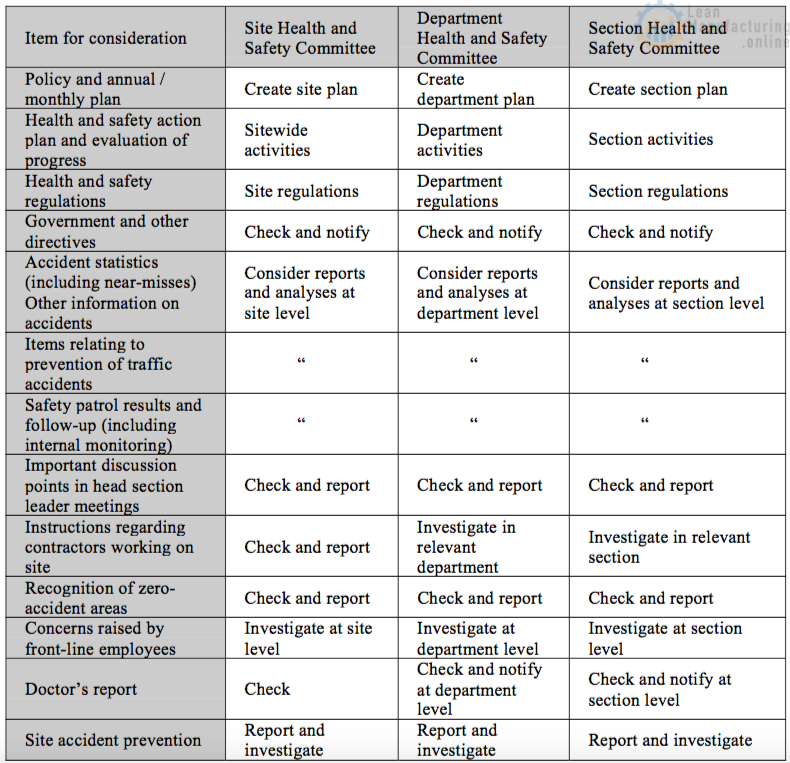

Establishing a Safety Management Organisation and Safety Committees

It is essential to build a system that delivers practical results throughout the company, whilst ensuring that relevant information is communicated properly and that those responsible for health and safety in each department pay constant attention to their health and safety duties. This can be achieved by setting up a safety management organisation divided up into various committees. The entire workforce must work together towards eliminating accidents and work-related illnesses (see Table 11.4).

Table 11.4

Reference 2

Items to Be Checked at the Preparation Stage

(The check sheet below shows the general items that should be checked, but in practice it is advisable to create a list of specific items for your own particular workplace).

|

•Have all the laws and regulations that the company must comply with been identified? |

|

•Have all the company’s internal rules and procedures been listed? |

|

•Have safety shortcomings in the company been highlighted by analysis of past accidents? |

|

•Have maps been created enabling accidents to be stratified in terms of mode, location, task, etc.? |

|

•Have health and safety checklists been drawn up? |

|

•Have a safety body and safety committees been set up? |

|

•Have all the tasks that must be done by a qualified operator been listed? |

Investigating and analysing, reviewing hazards, and making improvements

Provision and use of protective equipment

(1) Protective equipment

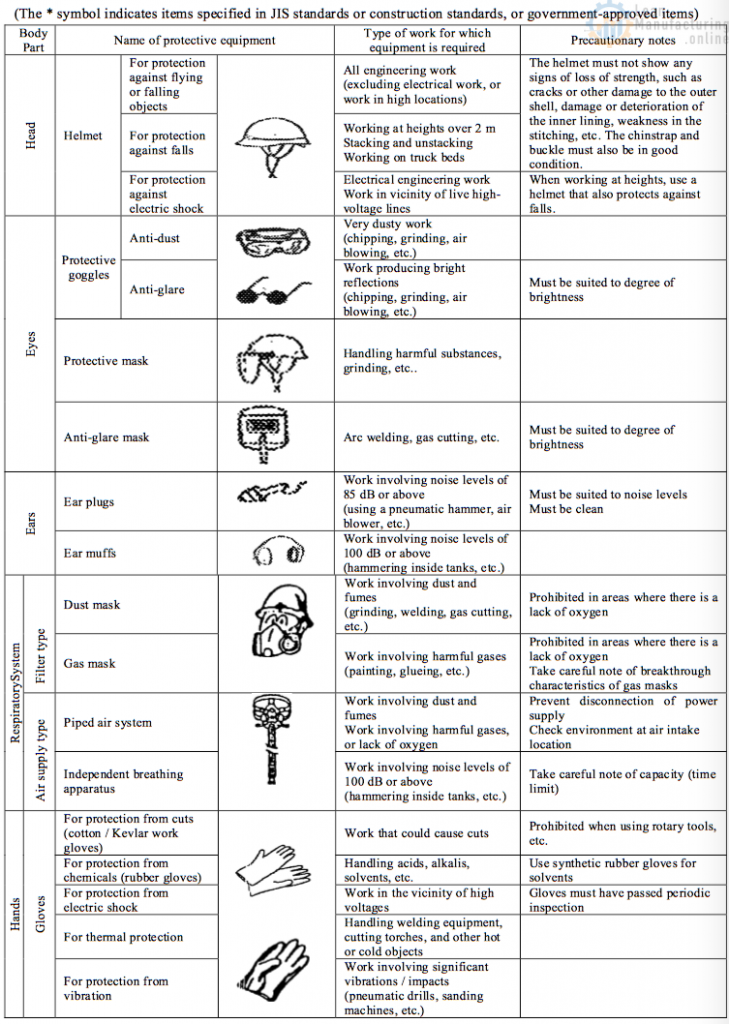

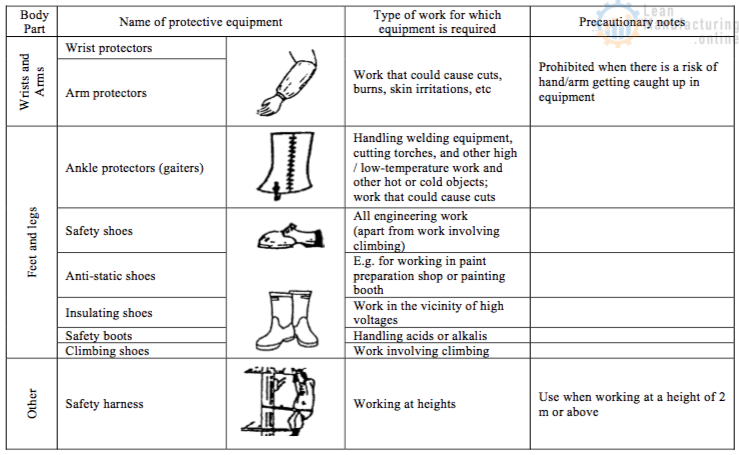

Certain tasks and processes require the use of protective equipment. Operators’ health and safety must be ensured by providing them with the right PPE (personal protective equipment) and getting them to use it. The right type of equipment must be selected by taking account all of the possible hazards that might occur during a task, and it must be used and looked after properly. Table 11.5 shows some typical items of protective equipment, with cautionary notes regarding their use.

Protective gear must allow the operator wearing it to carry out his or her work easily, without losing efficiency. It should provide adequate protection against the identified hazards, and be made from suitable materials. The equipment should also be well designed and finished, and be stored in a clean and tidy place when not in use, so that it is in good condition and ready for operators whenever they need it. Strict discipline is vital in the daily management of protective equipment, if items such as uniforms, helmets, safety shoes, eye protectors, safety harnesses, gloves, dust masks, ear protectors, and so on, are to fulfil their functions properly. There is absolutely no point in having protective gear if it does not serve its purpose when the danger actually arises.

Table 11.5 Typical Protective Equipment

(2) Correct use

Operators should begin by trying on the protective equipment specified for a particular task. It may feel hot, heavy or painful, or restrict their movement, and make the job hard to carry out. However, not wearing it can be suicidal. The first requirement is to ensure safety, but it is a good idea to improve protective equipment in various ways as long as safety is not compromised. The most urgent improvements are those aimed at making it easier for operators to perform their tasks, as well as enhancing the workplace itself to do away with the need for protective equipment wherever possible. More difficult issues should be developed further in subsequent steps.

Operators must learn to check the following points in order to establish basic safety conditions:

Clothes

Am I wearing the designated work clothes?

Are all my buttons done up properly?

Are my collar and cuffs done up?

Have I got anything in my pockets that is prohibited, or anything that I don’t need for my work? Are my clothes torn or split?

Are my clothes clean?

Safety helmet

Is the inner adjustment band set to the right size?

Are the required certification and approval marks, etc. shown on the helmet?

Am I wearing the designated helmet, or other type of headgear?

Is the chinstrap done up tightly?

Protective equipment

Am I using the designated safety glasses or goggles for the tasks and work locations they are specified for?

Are they clean?

Am I using the designated ear protectors for the tasks they are specified for?

Am I using the designated safety gloves for the tasks they are specified for?

Am I using the designated safety shoes for the tasks they are specified for?

Am I wearing my safety shoes properly, and are they laced up securely and comfortably? Am I wearing my leg protectors properly, if they are needed?

Working at heights

Am I wearing a designated safety harness for the tasks it is specified for?

When cleaning or doing other work at heights, has a curtain been suspended around the work to protect the surrounding area, and have people in the vicinity been warned?

Do not throw tools or other objects up or down to anyone.

Be careful not to drop any tools or other objects.

Other danger areas, etc.

Are hazard warning signs and ‘No Entry’ signs displayed in the correct places?

Operators should not, as a rule, enter designated danger areas. Operators must not enter prohibited areas.

Is the work floor area adequately illuminated?

Are passageways and work areas clearly marked by white lines, etc.?

Are there designated storage points for pallets and tools, and are these items stored properly according to the established standards?

Are any items left in the passageways or projecting into them?

Work requiring qualified operators

Small-scale heavy machinery, forklifts, shop-floor cranes, etc. must only be operated by qualified personnel.

Electrical work must only be carried out by qualified personnel.

Any other personnel without the proper qualifications authorised by the company must not do this type of work.

Small power tools, etc. must be inspected before use, to check that they are working properly. Carrying out work

The safety supervisor must be clearly identified, and that person’s instructions must be followed.

The safety supervisor must wear the required armband.

Before starting work, anticipate hazards, note all relevant warnings, ensure that the right protective equipment is being worn, and check people’s mental and physical condition.

Do not smoke whilst working; only smoke in the designated smoking areas.

Do not use fire or flames, e.g. welding, using cutting torches, etc., in areas where naked flames are prohibited.

When working as a team, appoint a team leader and follow his or her instructions.

When working as a team, decide on the signals to be used for coordinating the work and monitor other people’s actions as well as your own.

Checking and restoring safety devices

(1) Safety devices

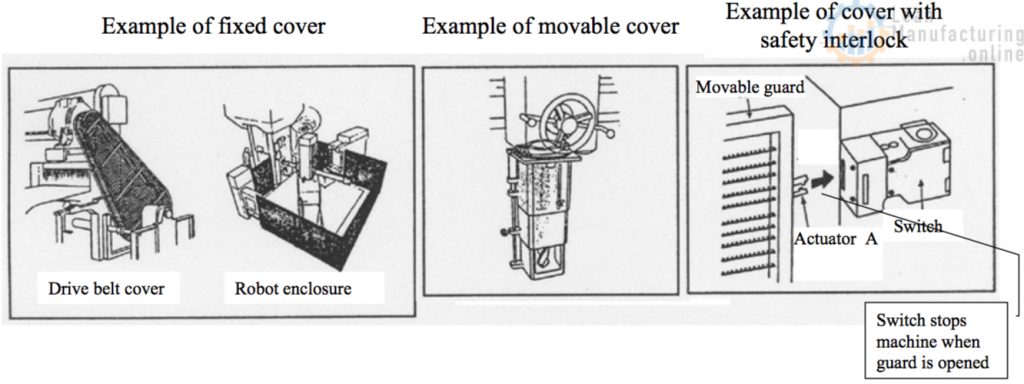

The need for safety devices arises because, unfortunately, people can be careless. Human error can easily lead to an accident, or inconvenience a customer, and safety devices are used to ensure that no harm occurs even if someone does something wrong. Examples include safety covers, error-proofing devices, safety colour codes and markings, guard rails, fire-proofing devices, and systems for preventing electric shocks, transport accidents, and so on.

A safety cover is a protective cover that prevents operators from getting clothing or body parts caught in the moving parts of a machine. Safety covers can also be used to stop operators from coming into contact with projecting machine parts or hazardous substances. All safety devices should be regularly inspected, and any problems corrected so that the devices can fulfil their functions and work correctly and reliably.

(2) Error-proofing and fail-safing

Error-proofing and fail-safing mean designing equipment and work procedures in such a way that safety can be guaranteed, even if an operator is careless and makes a mistake. After all, as the saying implies, ‘to err is human’, and it is in our nature to make mistakes occasionally, no matter how hard we try not to. We cannot rely simply on the attentiveness of operators to ensure safety at work – the key is to make our work processes and equipment intrinsically safe, so that they compensate for human lapses.

Error-proof design:

This type of design automatically guarantees safety and prevents an accident or incident from occurring even if the operator makes a mistake. Examples include an overwinding prevention device on a crane or hoist that stops the load from being raised above a certain height, and an optically-triggered shutdown system or two-hand start-button control mechanism incorporated into a mechanical press.

Fail-safe design:

This type of design ensures that equipment always shuts down safely even if something goes wrong. Two examples are an automatic fire extinguisher built into a portable oil stove (which automatically puts out any fire, even if the stove is tipped over by an earthquake, for instance), and a cord reel equipped with a residual current circuit breaker that automatically trips if an excessive current flows.

|

Shutting down equipment |

|

|

Are there clear rules on shutting down machinery in a way that guarantees safety? |

|

|

Is there a clear safety procedure for starting up and shutting down equipment? |

|

|

Is there a clear safety procedure for turning the power supply on and off? |

|

|

Is there a clear safety procedure for releasing residual pressure from pneumatic and hydraulic devices? |

|

|

Checking the operation of safety devices |

|

|

Does each machine have a power shutoff switch? Is the switch located near the work position and easy to operate? |

|

|

Are established signalling methods in place, e.g. bells, etc., to indicate when machinery that forms part of a combined operation is starting up? |

|

|

If a machine is liable to spray out cuttings and other debris, does it have a suitable guard or cover to contain them? |

|

|

Have any safety devices been intentionally removed? Have the operators forgotten to put any back after removing them? |

|

|

Have the safety devices been subjected to periodic operating tests? Have the results been properly recorded? |

|

|

Are the glass windows of optical sensors kept clean? |

|

|

Are temperature sensors installed at the correct positions? |

|

|

Are the emergency stop buttons clearly visible and easily accessible? |

|

|

Are residual current circuit breakers correctly installed? |

|

|

Are limit switches placed in the correct positions, and are the switch arms free to move? |

|

|

Checking safety in grinding machines |

|

|

Ensure that a rigid cover is fitted to every machine with a grinding wheel of 50 mm dia. or above, and check the following points: |

|

|

The machine should be test-run for at least one minute before starting work, and at least three minutes after changing the grinding wheel. |

|

|

Only the designated grinding face of the wheel should be used for grinding. |

|

|

The specified flange must be used when installing a grinding wheel. |

|

|

General checks |

|

|

Is everyone fully aware of statutory and company regulations? |

|

|

Have the required items of protective equipment been listed, and are they being used correctly? |

|

|

Are safety devices being checked and restored properly? |

|

|

Do operators understand the safety colour code systems in use? |

|

|

Do they understand the checkpoints listed above? |

|

|

Are passageways, piping, ducting, processes, equipment, etc., signed clearly and accurately? |

|

Accident mode countermeasures

In this step, the accident scenarios identified so far are re-examined, so that corrections can be made and action taken to prevent the same accident modes from reoccurring. This step is divided into separate sub-steps for each accident mode. The best approach is to start with the most common accident modes.

Each company must decide on the order to proceed in, on the basis of its own particular circumstances. In each sub-step, the list of checkpoints can be used to review safety and evaluate the situation before and after action was taken.

(1) Creating a plan

Establish an order for the sub-steps, giving priority to accident modes that have occurred most commonly or had the most serious consequences in the past. At the same time, devise countermeasures for those points that have not been dealt with properly in previous steps. Problems in the use of protective equipment must be rectified, and the workplace and job content must be improved wherever possible in order to remove the need for operators to wear protective gear. By implementing these activities in the same way for all the sub-steps, it is possible to eliminate these accident modes and the potential for accidents of this kind to occur.

Where radical countermeasures (i.e. hardware modifications) can be taken, they should be implemented without delay. If this type of action is not possible, then clear warning signs and other indicators should be used to ensure that all employees are aware of the potential hazard.

I need to refer Health Safety field

Hi Le Huan,

Thanks for your comment. Please let us know what kind of help you need about H & S. You can leave your request here or use the Contact form to get in touch with us.